Effectiveness of Didactic Audiovisual Translation and English for Social Purposes to Foster Language Skills and Gender Awareness

Efectividad de la Traducción Audiovisual Didáctica y del Inglés con Fines Sociales para fomentar las competencias lingüísticas y la perspectiva de género

Efectivitat de la Traducció Audiovisual Didàctica i de l’Anglès amb Finalitats Socials per Fomentar les Habilitats Lingüístiques i la Perspectiva de Gènere

Antonio-Jesús Tinedo-Rodríguez1

1 | Department of English and German, Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad de Córdoba

f12tiroa@uco.es

Received: 09/02/2024 | Accepted: 09/04/2024 | Published: 22/07/2024

Abstract

Exponential advancements in the technological field have opened numerous possibilities in the educational domain. In this regard, it is important to highlight the role of Didactic Audiovisual Translation (DAT), as it is a young field of knowledge that has developed in parallel with technologies. DAT involves the application of pedagogical translation to audiovisual texts, enabling students to become consumers and creators of audiovisual products through the application of adapted protocols from different modes of audiovisual translation (subtitling, dubbing, etc.). In addition, English for Social Purposes and Cooperation (ESoP) advocates for incorporating cross-curricular contents into language learning materials, allowing students not only to develop their language skills but also to simultaneously gain awareness of issues of social impact. The aim of this study is to explore to what extent the combination of ESoP and DAT is motivating for students and fulfils the goal of improving linguistic skills and social awareness simultaneously. The sample consisted of 32 participants. A didactic subtitling lesson plan focusing on the oppression of women’s creativity throughout history was implemented, followed by a questionnaire. The results indicate that participants perceived improvements in their language skills, gender awareness, and motivation. It is of interest that future studies explore other DAT modes and their combination with ESoP with longer interventions.

Keywords

didactic audiovisual translation; language education; educational technology; gender awareness

Resumen

Los avances exponenciales en el ámbito tecnológico han abierto numerosas posibilidades en el ámbito de educativo. En este sentido, cabe destacar el papel de la Traducción Audiovisual Didáctica (TAD), puesto que es un campo del conocimiento joven que ha tenido un desarrollo paralelo al desarrollo tecnológico. La TAD consiste en la aplicación de la traducción pedagógica al texto audiovisual, de forma que el alumnado se convierte en consumidor y creador de productos audiovisuales a través de la aplicación de protocolos adaptados de diferentes modalidades de traducción audiovisual (subtitulado, doblaje, etc.). Asimismo, el Inglés con Fines Sociales y de Cooperación (IFSyC) aboga por dotar de contenidos transversales al diseño de materiales para el aprendizaje de lenguas, de forma que el alumnado no solo desarrolle sus competencias lingüísticas, sino que de forma simultánea adquiera conciencia sobre diferentes temáticas sociales. El objetivo de este estudio es explorar hasta qué punto la unión del IFSyC y la TAD resulta motivadora para el alumnado y cumple con el cometido de mejorar las competencias lingüísticas y la conciencia social simultáneamente. La muestra consta de 32 participantes. Se implementó una unidad formativa de subtitulado didáctico que ponía el foco en la opresión a la creatividad de las mujeres en la historia y posteriormente se implementó un cuestionario. Los resultados muestran que las personas participantes percibieron una mejora de sus competencias lingüísticas, su conciencia de género y su motivación. Es de interés que estudios futuros exploren diferentes modalidades de TAD con intervenciones de mayor duración.

Palabras clave

traducción audiovisual didáctica; enseñanza de lenguas; tecnologías educativas; conciencia de género

Resum

Els avanços exponencials en el camp tecnològic han obert nombroses possibilitats en l’àmbit educatiu. Hi destaca la traducció audiovisual didàctica (TAD), que és un camp de coneixement incipient que ha tingut un desenvolupament paral·lel al tecnològic. La TAD consisteix a aplicar la traducció pedagògica al text audiovisual i que l’alumnat esdevinga consumidor i creador de productes audiovisuals alhora, a través de protocols adaptats de diferents modalitats de traducció audiovisual (subtitulació, doblatge, etc.). Així mateix, l’anglès amb finalitats socials i de cooperació (AFSiC) promou la incorporació de continguts transversals al disseny de materials per a l’aprenentatge de llengües, de manera que l’alumnat no desenvolupe només les seues competències lingüístiques, sinó que, simultàniament, es consciencie sobre diferents temàtiques socials. L’objectiu d’aquest estudi, la mostra del qual constava de 32 participants, és explorar fins a quin punt la unió de l’AFSiC i la TAD resulta motivadora per a l’alumnat i assoleix l’objectiu de millorar simultàniament les competències lingüístiques i la consciència social. Es va dur a la pràctica una unitat formativa de subtitulació didàctica que posava el focus en l’opressió a la creativitat de les dones en la història i posteriorment es va implementar un qüestionari. Els resultats mostren que les persones participants van percebre millora de les competències lingüístiques, la consciència de gènere i la motivació. Hom considera interessant que més estudis exploren en el futur diferents modalitats de TAD amb intervencions de major durada.

Paraules clau

traducció audiovisual didàctica; ensenyament de llengües; tecnologies educatives; consciència de gènere

Practitioner notes

What is already known about this topic

• Didactic subtitling is effective for the development of written production skills.

• Subtitling as a task fosters oral reception skills.

• The combination of English for Social Purposes and Cooperation and video game localization has shown positive results for the development of translation skills and gender awareness.

What this paper adds

• Participants’ perceptions of the combination of ESoP and DAT shows the potential of the combination of the approaches for the development of language skills in an integrated way.

• Participants believe that their awareness of gender equality has increased after the intervention.

• Motivation seems to be enhanced by the union of DAT and ESoP.

Implications for practice and/or policy

• Need to conduct experiments in different educational levels with DAT-based lesson plans including the ESoP approach with larger samples.

• Proof of the potential of cross-curricular knowledge.

1. INTRODUCTION AND REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

The exponential growth of technology has had important implications on the educational realm. In this regard, the new possibilities offered by personal computers widens the pedagogical horizon (Su & Zou, 2022). With respect to this, the last decades have seen increasingly rapid advances in the use of multimedia products for teaching purposes. The use of film and media in the language classroom is narrowly linked to the formerly mentioned advances, and the interest on that topic has increased in recent years. Building upon this point, Herrero & Vanderschelden (2019) explored the different possibilities for including media in foreign language education. They concluded that these possibilities range from fostering intercultural awareness through reflection on audiovisual content to making use of Audiovisual Translation (AVT, henceforth) in diverse ways.

Concerning the use of Audiovisual Translation, it is worth mentioning that according to Talaván (2010), it can be used as a task or a support for language learning. AVT as a support consists of the use of different AVT modes (subtitling, dubbing, etc.) to aid in the comprehension of specific audiovisual contents, whilst AVT as a task entails students applying adapted AVT protocols of particular AVT mode to a video excerpt (Talaván, 2020).

It was in the 80s when the first proposals and empirical research on the use of AVT as a support emerged, being the study by Vanderplank (1988) one of the pioneering ones in the use of subtitling as a support for language learning. Vanderplank’s (1988) study explored the pedagogical potential of subtitles for language learning with a sample which comprised 15 international students. These students were exposed to subtitled material for an hour each week for nine weeks. Their feedback indicated that subtitles were useful for language learning, even though two of them considered that the use of subtitled material was a marker of laziness. The fact that they found it useful to get familiar with authentic speech and unfamiliar accent is positive, and they reported low levels of language anxiety. Nonetheless, it was Díaz Cintas (1995) who made a proposal on the use of subtitling as a teaching technique, in other words, this proposal was a clear example of subtitling as a task.

Various investigations (Latifi, et al., 2011; Mulyani et al., 2022; Pujadas Jorba & Muñoz, 2020; among others) have examined the language gains derived from the implementation of tasks based on subtitles as a support. Frumuselu (2020) analyzed the implications of Cognitive Load Theory and the use of subtitled materials, and Vanderplank (2016) made a very interesting contribution which consists of distinguishing the “effects of” and the “effects with” captions and subtitles, suggesting that the “effects with” work at the language level (vocabulary, oral reception, etc.), but that the “effects of” have broader implications when it comes to enhancing the learning experience. Nonetheless, despite the proven benefits of using subtitles as a support in terms of language gains, it is interesting to examine the potential of subtitling as a task due to the fact that under this approach learners have a more active role and are supposed to produced audiovisual themselves (Tinedo-Rodríguez, 2022a).

It was at the turn of the millennium when international projects like LeViS (Learning via Subtitling) (Sokoli, 2006) began exploring the pedagogical potential of the use of AVT as a task in foreign language education. During this decade, the most studied AVT mode was subtitling because of the technical constraints that made revoicing more challenging. It is important to highlight that the field of study which explores the effects of the pedagogical use of AVT as a task is known as Didactic Audiovisual Translation (DAT, hencefort) (Talaván et al., 2024) and it delves into the six main AVT modes: didactic subtitling, didactic voice-over, didactic dubbing, didactic audio description, didactic subtitling for the deaf and hard of hearing, and didactic free commentary.

As mentioned before, didactic subtitling is the most studied DAT mode. Perhaps, it was during the first decade of the 21st century when strong empirical evidence of the use of didactic subtitling emerged. Proposals like the one by Talaván (2006b) delved into the potential of didactic subtitling for teaching English for Specific Purposes, in this case, English for Business. In this context, Talaván (2006a) developed specific guidelines on how to prepare the clips to be subtitled, and proposed a set of software for subtitling like Subtitle Workshop, Subtitul@m, or Fab Subtitler.

The important turn on the validity of didactic subtitling comes with empirical studies like the one by Talaván (2011) with a sample of 50 B1 English learners. This study proved the effectiveness of subtitling as a task for the development of oral reception skills as there were statistically significant differences in the measurement of the formerly mentioned skills between the control and the experimental groups. As new empirical studies (Talaván & Ávila-Cabrera, 2021; Talaván & Rodríguez-Arancón, 2014) on the effectiveness of didactic subtitling emerged, proposals focusing on various aspects such as interculturality (Borghetti, 2011) or motivation (Baños & Sokoli, 2015) also arose. Delving back into the subject of interculturality, Borghetti & Lertola (2014) conducted a qualitative case study with promising results that showed the potential of didactic subtitling for the development of cultural and intercultural awareness. Other studies like the one by Ávila-Cabrera (2021) proved empirically how reverse subtitling could foster writing skills within the context of an ESP course. Former studies by Ávila-Cabrera (2018) also reinforce this evidence. Furthermore, Ávila-Cabrera & Rodríguez-Arancón (2021) also conducted studies on the effects of didactic subtitling on writing skills in the context of Business English. In addition, intralingual captioning also proved to have a positive impact on writing according to the results of the iCap project (Talaván et al., 2016). Besides, the case of the OFFTATLED project (Rodríguez Arancón & Ávila-Cabrera, 2018) is particularly interesting because it focused on a cultural element often overlooked in traditional syllabuses, yet crucial for the development of language skills: taboo language. It is also important to highlight the study by Lertola (2019) which concluded that didactic subtitling proved to be effective for incidental vocabulary acquisition. The study involved 25 English students and consisted of an experimental design.

Reached this point, it is important to mention that the ClipFlair Project (Baños & Sokoli, 2015; Zabalbeascoa et al., 2012), which was a European project, played a pivotal role in the consolidation of DAT as a field of study, for it set the bases for the development of the ClipFlair platform which allowed learners to engage in captioning or revoicing tasks in online free environments. Many studies derived from that project proved the effectiveness of different DAT modes for language learning like the one by Navarrete (2013) focusing on didactic dubbing for Spanish as a Foreign Language teaching, or the one by Incalcaterra McLoughlin & Lertola (2015) that focused on the combination of didactic subtitling and didactic revoicing for teaching Italian online. In addition to language teachers, ClipFlair also caught the attention of translator trainers (Gajek, 2016) and empirical experiments were conducted in Poland assessing students’ participation and attitudes. Besides, in the Italian context, proposals like the one by Lertola (2016) delved into new possibilities of didactic subtitling for the development of integrated skills.

Another significant project was the TRADILEX project. This project involved a large-scale empirical validation of DAT-based intervention to test the effectiveness of the intervention on English adult learners. The methodological proposal was set by Talaván & Lertola (2022) and consisted of 15 lesson plans with a fixed structure: warm-up, video viewing, DAT task, and post-DAT task. The sequence included 3 didactic subtitling lesson plans, 3 didactic voice-over lesson plans, 3 dubbing lesson plans, 3 didactic AD lesson plans, and 3 didactic SDH lesson plans. Each lesson plan was designed to last 60 minutes. The first two sections of the lesson plans, warm-up, and video viewing, served as introductions, aiming to equip learners with the necessary knowledge to tackle the DAT task. This task involved of carrying out the translation task while following the protocols for a particular DAT mode. It is worth mentioning that DAT protocols are more flexible than those used by professional AVT practitioners due to the fact that the main purpose is not to train translators, but to provide language learners with tools to develop their skills. Specific instruments like the Initial and Final tests for Integrated Skills were designed and validated (Couto-Cantero et al., 2021) within the context of the project, and the objective of these instruments was to measure the development of language skills: oral and written reception, and oral and written production. Before conducting the main experiment, a series of piloting experiences proved the effectiveness of different DAT modes like didactic AD (audio description) (Couto-Cantero et al., 2022; Plaza Lara & Gonzalo Llera, 2022), didactic SDH (subtitling for the d/Deaf and hard of hearing) (Bolaños García-Escribano & Ogea-Pozo, 2023; Tinedo-Rodríguez & Frumuselu, 2023), didactic subtitling (Plaza Lara & Fernández Costales, 2022) or the combination of accessibility modes (Talaván et al., 2022). In relation to topics raised by Borghetti (2011), Rodríguez-Arancón (2023) empirically demonstrated how participants perceived that DAT-based interventions fostered their intercultural awareness, motivation, and cross-curricular skills like ICT skills. The results of the TRADILEX project showed that the sequences and the methodological approach proposed by Talaván & Lertola (2022) were effective for oral and written reception, and oral and written production, according to the results published by Fernández-Costales et al. (2023). The sample comprised 566 participants and the study had a quantitative nature.

Apart from adult education, Fernández-Costales (2014) explored the potential of didactic subtitling in Primary education and concluded that it fostered students’ motivation. Fernández-Costales (2021a) also conducted an experiment involving 120 Primary Education students from 10 different schools to explore their perceptions on the combination of didactic subtitling and dubbing. The study concluded that students showed a slight preference for dubbing, and participants’ perceptions were positive. It is worth mentioning that DAT-based tasks showed positive synergies with Content Language Integrated Learning and that teachers (Fernández-Costales, 2021b) and students (Fernández-Costales, 2014) perceive that DAT is a suitable educational resource in CLIL settings. Besides, Gómez-Parra (2018) reinforces the findings by Fernández-Costales (2021b) with a proposal on the combination of DAT and CLIL. In the realm of English for Specific Purposes and in the context of the TRADILEX Project, several studies (Gonzalez-Vera, 2021, 2022) proved the benefits in terms of language gains of didactic subtitling. DAT has essentially been developed thanks to teaching innovation projects. In addition, there have been large-scale national and international projects such as LeViS, ClipFlair, PluriTAV or TRADILEX that have represented a significant advancement in knowledge. Researchers have focused on the effects of didactic subtitling on language learning. Furthermore, other studies have focused on CLIL or ESP proving the effectiveness of DAT in bilingual contexts or in the teaching of specialized languages.

Talaván & Tinedo-Rodríguez (2023) delved into the interdisciplinary nature of DAT, and explored its relationship with CLIL (Content Language Integrated Learning) and other emerging approaches to language learning. The authors highlighted the importance of exploring the synergies between DAT and English for Social Purposes and Cooperation (ESoP, hencerforth). ESoP is a term coined by Huertas-Abril & Gómez-Parra (2018) and consists of the inclusion of social issues within the language classroom to foster both language skills and social awareness on topics which are connected to the reality of students like racism, gender equality or the environment. Palacios-Hidalgo & Huertas-Abril (2021) conducted a teacher training in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic which consisted of providing pre-service teachers with training to design ESoP-based lesson plans to provide schools with resources for language learning within the context emergency remote language teaching.

Despite the effectiveness of ESoP and DAT, there is still a gap which consists of exploring the effectiveness of the combination of DAT and ESoP approaches in language education. To the author’s knowledge, only Ogea Pozo (2023) has researched the combination of DAT and ESoP by delving into the topic of gender equality. The DAT mode of the experiment conducted by Ogea Pozo (2023) was video game localization, and the author delved into participants’ perception of their development of translation skills according to the framework stablished by Hurtado-Albir (1999). The results showed that the skills that participants perceived to have developed the most are extralinguistic competences. Nonetheless, literature specifically addressing language learning and awareness on social topics is still scarce for Ogea Pozo (2023) focused on translation skills.

This study has the objective of examining the perception of language learners on the potential of didactic subtitling for developing language and cross-curricular skills, specifically addressing the ESoP dimension of gender equality awareness. In this case, the proposal consists of the translation of a short excerpt on a video by Virginia Woolf, and Spanish learners were expected to produce an English version of the subtitles. In simpler terms, reverse translation involves translating from the second language (L2) back to the first language (L1). According to Díaz Alarcón & Menor (2013) this process offers significant benefits for language learning because it presents cognitive and translation challenges that aid in the development of language skills. The research questions which will be addressed are the following ones:

RQ1. Do participants perceive an improvement in their language skills due to the intervention?

RQ2. Does the inclusion of the gender perspective foster motivation?

RQ3. Are there statistically significant differences in the perception of the use of DAT-based lesson plans designed under the ESoP approach according to gender? This study thus aims at testing the effectiveness of subtitling as a task to enhance both language skills and gender awareness, and it also has the objective of exploring whether this proposal which combines DAT and ESoP fosters motivation.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

This research had a mixed nature and consisted of the implementation of a lesson plan on didactic subtitling which aimed at developing awareness on gender equality and language skills. There was no control group, so it was a quasi-experimental post-test design. Participants were students enrolled in a course on General Translation at the UNED (Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia) who were offered the opportunity to voluntarily take part in the experiment, and the sample consisted of 32 participants, 25.0 % (N = 8) were men, and 75% (N = 32) were women. It is thus a convenience sample, as the participants were not selected randomly from the entire population but rather were chosen because of their availability and willingness to take part in the experiment.

The materials which have been employed consists of a didactic subtitling lesson plan that follows Talaván’s & Lertola’s (2022) structure, and which is based on Huertas’s & Gómez-Parra’s (2018) principles for the design of ESoP-based language learning materials. The lesson plan (https://forms.gle/ucF8PeLyM5SAany89) based on a former proposal by Tinedo-Rodríguez (2022b) for didactic voice-over is divided into four sections:

a)Warm-up: this section includes a written reception task, with mediation, use of English, and grammar activities which focus on conditional sentences. The texts, activities, and tasks focus on the role of women in history so as to provide students with awareness in this regard.

b)Video viewing: the video was produced within the context of the Tradilex project, and it is a short film (https://youtu.be/eIQc009q6_g?si=j_erA4vu6EB8DaPJ) about a Room of One’s Own in Spanish. The section includes mediation and reverse translation activities. Gender is included due to the fact that the video is about women and the historical oppression on their creativity (Goodman, 2013).

c)Didactic subtitling task: Students were provided with specific guidelines on how to subtitle taking subtitle’s length and duration into account, together with condensation and segmentation strategies. The use of these strategies in any of the language combinations makes students focus on the linguistics of subtitling (Díaz-Cintas & Remael, 2021), which is of utmost importance for the development of skills. The software they have worked with is AEGISUB, because even though it is sometimes used by professionals, it also meets the needs of subtitling with educational purposes.

d)Final task: This oral production task consisted of asking participants to put themselves into Judith Shakespeare shoes. As the hypothetical sister of William Shakespeare, Judith was assumed to possess the same level of talent as her brother. Participants were prompted to speculate on Judith’s hypothetical life trajectory and whether she could have achieved comparable success. Through this exercise, participants were encouraged to confront gender dynamics in historical contexts, contemplating the barriers Judith might have faced in realizing her artistic potential. The task fostered spontaneous reflection on the role of gender in shaping historical narratives and artistic legacies.

Participants were allotted a two-week period, spanning from March 26th, 2023, to April 15th, 2023, to fulfill the task requirements and submit the questionnaire. This process was facilitated through Moodle, employing a forum for addressing any inquiries or clarifications that participants may have.

The research questions (RQ) of this study are the following ones:

RQ1. Do participants perceive an improvement in their language skills due to the intervention?

RQ2. Does the inclusion of the gender perspective foster motivation?

RQ3. Are there statistically significant differences in the perception of the use of DAT-based lesson plans designed under the ESoP approach according to gender?

To answer these questions, quantitative and qualitative analysis have been employed as the instrument which was developed (https://forms.gle/AgUu3Cwnei2LLmfB7) consisted of an ad hoc questionnaire that contained items to measure participants’ perceptions by means of a 10 points Likert-scale set of questions, and an open question for the express their opinions. Items 8-20 of the questionnaire conform the items linked to the combination of ESoP and DAT. The questionnaire is reliable since Cronbach’s α (.875) is above the threshold of 0.7, and both, the lower and upper limits of the 95% confidence interval (.746 to.913, respectively) indicate that the instrument is consistent and reliable.

3. ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

This section has the objective of exploring participants’ perceptions on different aspects of the intervention. To do so, each RQ will be addressed separately.

RQ1. Do participants perceive an improvement in their language skills due to the intervention?

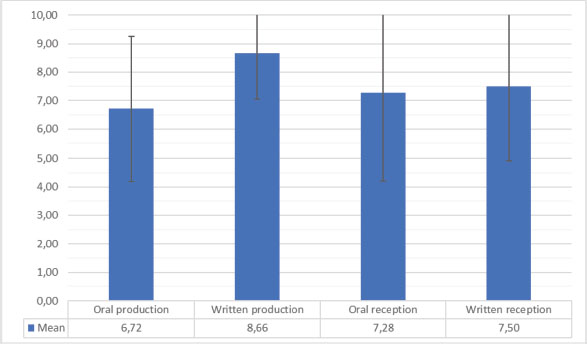

The questionnaire measured to which extent participants perceive to have developed each skill on a scale which ranges from 0 to 10 as shown on Figure 1. Participants perceive that the skill they have developed the most was written production (M = 8.66, SD = 1.59; Saphiro-Wilk =.812, p-value = <.001), followed by written reception (M = 7.50, SD = 2.58; Saphiro-Wilk =.822, p-value = <.001), and then followed by oral reception (M = 7.28; SD = 3.06; Saphiro-Wilk =.809, p-value = <.001). In this regard, participants reported that the skill they have developed the least was oral production (M= 6.72; SD = 2.53; Saphiro-Wilk =.923, p-value = <.024). According to the values obtained in the Saphiro-Wilk test, the date deviate from normality.

Figure 1. Participants’ perceptions on their development of their language skills. Source: Author’s own elaboration

Table 1 explores the correlations among participants’ perceptions on how the lesson plan helped them develop their skills, and the perceived degree of motivation induced by the inclusion of gender perspectives (due to the ESoP approach) in their learning process. According to the data obtained significant correlations were found between perceived improvement of oral and written production (Spearman’s ρ =.383; p-value =.015), written production and reception (Spearman’s ρ =.423; p-value =.008), and motivation and written production (Spearman’s ρ =.383; p-value =.015). It is important to mention that due to the sample size (N = 32) and the lack of normality for each item, a non-parametric test (Spearman’s ρ) has been implemented to delve into the correlation among the variables.

Table 1. Correlation among perceptions on the development of language skills and perceived motivation due to the inclusion of gender. Source: Author’s own elaboration

Variable |

Statistics |

Oral production |

Written production |

Oral reception |

Written reception |

Motivation due to ESoP contents (gender) |

Oral production |

Spearman’s ρ |

1.000 |

.383* |

0.111 |

.170 |

.029 |

p-value |

|

.015 |

.272 |

.176 |

.438 |

|

N |

32 |

32 |

32 |

32 |

32 |

|

Written production |

Spearman’s ρ |

.383* |

1.000 |

0.235 |

.423** |

.383* |

p-value |

.015 |

|

.098 |

.008 |

.015 |

|

N |

32 |

32 |

32 |

32 |

32 |

|

Oral reception |

Spearman’s ρ |

.111 |

.235 |

1.000 |

.778** |

.019 |

p-value |

.272 |

.098 |

|

.000 |

.460 |

|

N |

32 |

32 |

32 |

32 |

32 |

|

Written reception |

Spearman’s ρ |

.170 |

.423** |

.778** |

1.000 |

0096 |

p-value |

.176 |

.008 |

.000 |

|

.300 |

|

N |

32 |

32 |

32 |

32 |

32 |

|

Motivation due to ESoP Contents (gender) |

Spearman’s ρ |

.029 |

.383* |

.019 |

.096 |

1.000 |

p-value |

.438 |

.015 |

.460 |

.300 |

|

|

N |

32 |

32 |

32 |

32 |

32 |

These findings underscore the interconnectedness between perceived skill development, motivation, and the integration of gender perspectives in the learning process facilitated by the combination of DAT and ESoP.

RQ2. Does the inclusion of the gender perspective foster motivation?

There was an specific item in the questionnaire which ranged from 0 to 10, and it was “I find it motivating that gender perspective is included in the design of language learning task”. The main purpose of this item was to explore whether participants found motivating the inclusion of the gender perspective. The average score was 8,71 (SD = 2,275), being the lowest score (2) and the highest score (10).

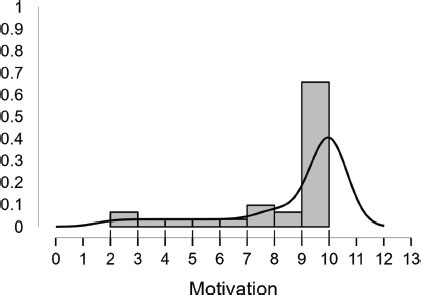

Figure 2 shows the distribution plot of the answers to this question, and it is interesting to highlight that it does not follow a normal distribution according to the Saphiro-Wilk test (Saphiro-Wilk =.637, p-value <.001). The distribution is negatively skewed (skewness = -1.837), and leptokurtic (2.407). It means that the distribution is skewed to the left, and that the peak is sharper than the one of a normal distribution. In other words, participants answers showed a consistent tendency toward high marks, being both, the median and the mode, 10. It can be thus concluded that participants found the inclusion of the ESoP approach motivating.

Figure 2. Participants’ perceptions on motivational aspects due to the inclusion of gender. Source: Author’s own elaboration

RQ3. Are there statistically significant differences in the perception of the use of DAT-based lesson plans designed under the ESoP approach according to gender?

The items shown in Table 2 were gathered through the questionnaire and focused on the development of gender awareness due to the intervention. The data have been analyzed categorizing the respondents by their gender to explore the level of motivation by male or female participants (there were not non-binary participants according to the data gathered).

Table 2. Descriptive data and t-test on the items on ESoP, categorized by gender. Source: Author’s own elaboration

Item |

Statistics |

Mean |

SD |

||||

t |

df |

p |

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

|

This lesson plan has helped me reflect on the presence of patriarchal thinking in English culture and in my own culture |

1.893 |

30 |

.034 |

9.750 |

8.333 |

.463 |

2.078 |

This lesson plan has helped me improve my awareness of gender-related issues. |

1.862 |

30 |

.036 |

9.750 |

8.208 |

.463 |

2.303 |

I consider this type of task important for highlighting the contributions of women to knowledge. |

.450 |

30 |

.328 |

9.375 |

9.042 |

1.768 |

1.829 |

This lesson plan has prompted me to reflect on the role of women in history. |

.587 |

30 |

.281 |

9.250 |

8.833 |

1.753 |

1.736 |

After completing this lesson plan. I feel that my level of commitment to equality has increased. |

.529 |

30 |

.300 |

8.250 |

7.625 |

1.982 |

3.118 |

I find it motivating that gender perspective is included in the design of language learning tasks. |

.577 |

30 |

.284 |

9.125 |

8.583 |

1.808 |

2.430 |

Male participants affirmed to have reflected on the presence of patriarchal thinking in the L2 and L1 cultures (M = 9.750, SD=.463) and the difference between the responses by male and female participants was statistically significant (p-value =.034). It should be carefully interpreted, it does not mean that men reflected in deeper way on these differences due to women having a obtained a lower score (M = 8.333, SD= 2.078). The reason is probably that female participants were already aware of these differences, and that is why male participants marked lower. This suggests that the intervention may effectively foster awareness among individuals who may have had less prior engagement with the topic.

The same trend is observed with the item “This lesson plan has helped me improve my awareness of gender-related issues” since the differences between male and female participants are statistically significant since the p-value (.036) shows that male participants (M = 9.750, SD=.463) reported a higher score than female participants (M = 8.208, SD= 2.303). However, for the remaining items, there were no statistically significant differences. Nevertheless, at the descriptive level, male participants consistently obtained higher results, which is consistent with the effectiveness of the intervention in reaching participants who may be less familiar with the topic. It can be concluded that the proposal enhances language awareness.

4. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

This study aimed at exploring whether the combination of ESoP and DAT was perceived as effective in terms of language gains, and if this combined approach fostered awareness on social issues and language skills integrated. Participants reported having developed writing skills the most which is coherent with empirical evidence from former studies on the effectiveness of didactic subtitling (Ávila-Cabrera, 2018, 2021; Ávila-Cabrera & Rodríguez-Arancón, 2021; Talaván & Ávila-Cabrera, 2021). It is important to mention that Talaván (2011) proved the effectiveness of didactic subtitling for the development of oral reception skills. Consequently, participants in this study perceived that this skill is the second-most developed, and results are thus in harmony with the existing literature.

Fernández-Costales (2021a) or Baños & Sokoli (2015) delved into the question of motivation. Fernández-Costales (2021a) conducted a study in Primary Education and students were motivated towards the combination of CLIL and DAT. This study contributes to the existing literature by demonstrating that adult language learners found the inclusion of cross-curricular content in DAT-based lesson plans motivating, aligning with previous findings which focused on other educational levels, and which dealt with curricular contents. Therefore, it can be concluded that the integration of language learning with DAT, whether through the CLIL or ESoP approaches, is perceived as motivating. DAT-based lesson plans appear to be considered motivating when combined with curricular or cross-curricular content. Nonetheless, these assertions should be made with caution since the lesson plan has been implemented with a small convenience sample. In this regard, it is important to highlight that further studies empirical studies with larger samples are needed.

In terms of gender awareness, Ogea-Pozo (2023) conducted a similar proposal for the DAT mode of video game localization and her results showed that participants perceived that they competences they developed the most were the extralinguistic ones, according to the framework on translation competences stablished by Hurtado-Albir (1999). These competences are linked to translators’ ability to integrate both their general and subject-specific knowledge in their practice. In this case, according to the results shown in Table 2, this proposal also seems to have developed participants’ knowledge about the role of women in history and their capacity to reflect on gender issues, which is one of the main purposes of ESoP (Huertas-Abril & Gómez-Parra, 2018). A comparison of the results obtained by male and female participants may results surprising at first sight because male perceptions on the effects of the intervention in terms of gender awareness were quantitatively higher, but these results were carefully interpreted, since it did not mean that men had more awareness on gender equality after the intervention. It is more likely that women had already higher levels of gender awareness. In this regard, the intervention appeared effective for participants with lower levels of familiarity with gender issues, demonstrating the educational potential of the proposal.

In conclusion, the current proposal has proved that the combination of ESoP and DAT could result effective in terms of language gains and also in fostering awareness on social issues. In this particular case, the focus has been on gender equality, but there is a wide horizon to explore as the ESoP approach consists of including cross-curricular contents which deal with social issues like poverty, racism, the environment, or peace. When it comes to DAT, it is important to explore different DAT modes like didactic dubbing or didactic SDH, among others. This study was exploratory and therefore the findings should be considered within the context in which it has been conducted. Further studies with larger samples, longer interventions, and the use of different DAT modes are required to delve into the union of ESoP and DAT.

REFERENCES

Ávila-Cabrera, J. J. (2018). TeenTitles. Implementation of a methodology based on Teenage subTitles to improve written skills. In John D. Sanderson & Carla Botella-Tejera (Eds.), Focusing on Audiovisual Translation Research (pp. 19–40). Publicacions Universitat de València.

Ávila-Cabrera, J. J. (2021). Reverse Subtitling in the ESP Class to Improve Written Skills in English: A Case Study. Journal of Audiovisual Translation, 4(1), 27–49. https://doi.org/10.47476/jat.v4i1.2021.22

Ávila-Cabrera, J. J., & Rodríguez-Arancón, P. (2021). The use of active subtitling activities for students of Tourism in order to improve their English writing production. Ibérica: Revista de La Asociación Europea de Lenguas Para Fines Específicos, 41, 155–180. https://doi.org/10.17398/2340-2784.41.155

Baños, R., & Sokoli, S. (2015). Learning foreign languages with ClipFlair: Using captioning and revoicing activities to increase students’ motivation and engagement. In K. Borthwick, E. Corradini, & A. Dickens (Eds.), 10 Years of the LLAS Elearning Symposium: Case Studies in Good Practice. (pp. 203–213). Research-Publishing.net.

Bolaños García-Escribano, A., & Ogea-Pozo, M. (2023). Didactic audiovisual translation Interlingual SDH in the foreign language classroom. Translation and Translanguaging in Multilingual Contexts, 9(2), 187–215. https://doi.org/10.1075/ttmc.00108.bol

Borghetti, C. (2011). Intercultural Learning Through Subtitling: The Cultural Studies Approach. In L. Incalcaterra McLoughlin, M. Biscio, & N. Mhainnìn (Eds.), Audiovisual Translation: Subtitles and Subtitling. Theory and Practice (pp. 111–138). Peter Lang.

Borghetti, C., & Lertola, J. (2014). Interlingual subtitling for intercultural language education: a case study. Language and Intercultural Communication, 14(4), 423–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2014.934380

Couto-Cantero, P., Sabaté-Carrové, M., & Gómez Pérez, M. C. (2021). Preliminary design of an Initial Test of Integrated Skills within TRADILEX: an ongoing project on the validity of audiovisual translation tools in teaching English. Research in Education and Learning Innovation Archives, 27(2), 73–88. https://ojs.uv.es/index.php/realia/article/view/20634

Couto-Cantero, P., Sabaté-Carrové, M., & Tinedo-Rodríguez, A. (2022). Effectiveness and Assessment of English Production Skills through Audiovisual Translation. Current Trends in Translation Teaching and Learning E, 149–182. https://doi.org/10.51287/cttl20225

Díaz Alarcón, S., & Menor, E. (2013). La traducción inversa, instrumento didáctico olvidado en el aprendizaje de lenguas extranjeras. Lenguaje y Textos, 38, 169–178.

Díaz Cintas, J. (1995). El subtitulado como técnica docente. Vida Hispánica, 12, 10–14.

Díaz-Cintas, J., & Remael, A. (2021). Subtitling. Concepts and Practices. Routledge.

Fernández-Costales, A. (2014). Teachers’ Perception on the Use of Subtitles as a Teaching Resource to Raise Students’ Motivation when Learning a Foreign Language. ICT for Language Learning, 426–430. https://conference.pixel-online.net/files/ict4ll/ed0007/FP/0932-LTT574-FP-ICT4LL7.pdf

Fernández-Costales, A. (2021a). Audiovisual translation in primary education. Students’ perceptions of the didactic possibilities of subtitling and dubbing in foreign language learning. Meta, Journal Des Traducteurs, 66(2), 280–300. https://doi.org/10.7202/1083179ar

Fernández-Costales, A. (2021b). Subtitling and Dubbing as Teaching Resources in CLIL in Primary Education: The Teachers’ Perspective. Porta Linguarum, 36, 175–192. https://doi.org/10.30827/portalin.v0i36.16228

Fernández-Costales, A., Talaván, N., & Tinedo-Rodríguez, A. J. (2023). Didactic audiovisual translation in language teaching: Results from TRADILEX. Comunicar, 31(77), 21–32. https://doi.org/10.3916/C77-2023-02

Frumuselu, A. D. (2020). The implications of Cognitive Load Theory and exposure to subtitles in English as a Foreign Language (EFL). Translation and Translanguaging in Multilingual Contexts, 4(1), 55–76. https://doi.org/10.1075/bct.111.ttmc.00004.fru

Gajek, E. (2016). Translation revisited in audiovisual teaching and learning contexts on the example of Clipflair project. In M. Marczak and J. Krajka (Eds.), CALL for Openness (pp. 73–90). Peter Lang. https://doi.org/10.3726/978-3-653-06756-9

Gómez-Parra, M. E. (2018). El uso de la traducción audiovisual (TAV) en el aula AICLE. In M. A. García-Peinado & I. Ahumada Lara (Eds.), Traducción literaria y discursos traductológicos especializados (pp. 463–481). Peter Lang.

Gonzalez-Vera, P. (2021). Building bridges between audiovisual translation and English for Specific Purposes. Ibérica: Revista de La Asociación Europea de Lenguas Para Fines Específicos (AELFE), 41, 83–102. https://doi.org/10.17398/2340-2784.41.83

Gonzalez-Vera, P. (2022). The integration of audiovisual translation and new technologies in project-based learning: an experimental study in ESP for engineering and architecture. DIGILEC: Revista Internacional de Lenguas y Culturas, 9, 261–278. https://doi.org/10.17979/digilec.2022.9.0.9217

Goodman, L. (2013). Literature and Gender. In Literature and Gender. Routledge.

Herrero, C., & Vanderschelden, I. (2019). Using Film and Media in the Language Classroom: Reflections on Research-led Teaching. Multilingual Matters.

Huertas-Abril, C. A., & Gómez-Parra, M. E. (2018). Inglés para fines sociales y de cooperación: Guía para la elaboración de materiales. Graò.

Hurtado-Albir, A. (1999). La competencia traductora y su adquisición. un modelo holístico y dinámico. Perspectives: Studies in Translatology, 7(2), 177–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.1999.9961356

Incalcaterra McLoughlin, L., & Lertola, J. (2015). Captioning and Revoicing of Clips in Foreign Language Learning-Using ClipFlair for Teaching Italian in Online Learning Environments. In C. Ramsey-Portolano (Ed.), The Future of Italian Teaching (pp. 55–69). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Latifi, M; Mobalegh, A. & Mohammadi, E. (2011). Movie subtitles and the improvement of listening comprehension ability: Does it help? The Journal of Language Teaching and Learning, 1(2), 18–29.

Lertola, J. (2016). La sottotitolazione per apprendenti di italiano L2. In A. Valentini (Ed.), L’input per l’acquisizione di L2: strutturazione, percezione, elaborazione (pp. 153–162). Cesati editore.

Lertola, J. (2019). Second Language Vocabulary Learning through Subtitling. Revista Española de Lingüística Aplicada/Spanish Journal of Applied Linguistics, 32(2), 486–514. https://benjamins.com/catalog/resla.17009.ler

Mulyani, M., Yusuf, Y. Q., Trisnawati, I. K., Syarfuni, S., Qamariah, H., & Wahyuni, S. (2022). Watch and Learn: EFL Students’ Perceptions of Video Clip Subtitles for Vocabulary Instruction. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 30(S1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.47836/pjssh.30.S1.01

Navarrete, M. (2013). El doblaje como herramienta de aprendizaje en el aula de español y desde el entorno Clipflair. MarcoELE, 16, 75–87.

Ogea Pozo, M. (2023). Fomentando la creatividad en el aula desde una perspectiva de género: la traducción audiovisual didáctica aplicada al videojuego “Vona.” EPOS. Revista de Filología, 186–210.

Palacios-Hidalgo, F. J., & Huertas-Abril, C. A. (2021). The Potential of English for Social Purposes and Cooperation for Emergency Remote Language Teaching: Action Research Based on Future Teachers’ Opinions. In A. Slapac, P. Balcerzak, & K. O’Brien (Eds.), Handbook of Research on the Global Empowerment of Educators and Student Learning Through Action Research (pp. 68–90). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-6922-1.ch004

Plaza Lara, C., & Fernández Costales, A. (2022). Enhancing communicative competence and translation skills through active subtitling: a model for pilot testing didactic Audiovisual Translation (AVT). Revista de Lenguas Para Fines Específicos, 28.2, 16–31. https://doi.org/10.20420/rlfe.2022.549

Plaza Lara, C., & Gonzalo Llera, C. (2022). Audio description as a didactic tool in the foreign language classroom: a pilot study within the TRADILEX project. DIGILEC: Revista Internacional de Lenguas y Culturas, 9, 199–216. https://doi.org/10.17979/digilec.2022.9.0.9282

Pujadas Jorba, G., & Muñoz, C. (2020). Examining adolescent efl learners’ tv viewing comprehension through captions and subtitles. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 42(3), 551–575. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263120000042

Rodríguez-Arancón, P. (2023). Developing L2 Intercultural Competence in an Online Context through Didactic Audiovisual Translation. Languages, 8(3), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030160

Rodríguez Arancón, P., & Ávila-Cabrera, J. J. (2018). The OFFTATLED project: OFFensive and TAboo Exchanges SubtiTLED by online university students. Encuentro, 27, 204–219.

Sokoli, S. (2006). Learning via subtitling (LvS). A tool for the creation of foreign language learning activities based on film subtitling. In M. Carroll & H. Gerzymisch-Arbogast (Eds.), Copenhagen conference MuTra: Audiovisual. 1-5 May (pp. 66–73). https://www.euroconferences.info/proceedings/2006_Proceedings/2006_Sokoli_Stravoula.pdf

Su, F., & Zou, D. (2022). Technology-enhanced collaborative language learning: theoretical foundations, technologies, and implications. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(8), 1754–1788. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1831545

Talaván, N. (2006a). Using subtitles to enhance foreign language learning. Porta Linguarum Revista Interuniversitaria de Didáctica de Las Lenguas Extranjeras, 6, 41–52 https://doi.org/10.30827/digibug.30659

Talaván, N. (2006b). Using the Technique of Subtitling to Improve Business Communicative Skills. Revista de Lenguas Para Fines Específicos, 12, 313–346. https://ojsspdc.ulpgc.es/ojs/index.php/LFE/article/view/170

Talaván, N. (2010). Subtitling as a Task and Subtitles as Support: Pedagogical Applications. In J. Díaz Cintas, A. Matamala, & J. Neves (Eds.), New Insights into Audiovisual Translation and Media Accessibility (pp. 285–299). Rodopi. http://www.nuigalway.ie/sub2learn/downloads/talavn_2010_subtiling_as_a_task_and_subtitles_as_a_support.pdf

Talaván, N. (2011). A Quasi-Experimental Research Project on Subtitling and Foreign Language Acquisition. In L. Incalcaterra McLoughlin, M. Biscio, & M. Á. Ní Mhainnín (Eds.), Subtitles and Subtitling. Theory and Practice (pp. 197–218). Peter Lang. https://doi.org/10.3726/978-3-0353-0167-0

Talaván, N. (2020). The Didactic Value of AVT in Foreign Language Education. In L. Bogucki & M. Deckert (Eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Audiovisual Translation and Media Accessibility (pp. 567–592). Palgrave Macmillan.

Talaván, N., & Ávila-Cabrera, J. J. (2021). Creating collaborative subtitling communities to increase access to audiovisual materials in academia. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 15(1), 118–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2021.1880305

Talaván, N., & Lertola, J. (2022). Audiovisual translation as a didactic resourse in foreign language education. A methodological proposal. Encuentro: Revista de Investigación e Innovación En La Clase de Idiomas, 30, 23–39. http://www3.uah.es/encuentrojournal/index.php/encuentro/article/view/66

Talaván, N., Lertola, J., & Costal, T. (2016). iCap: Intralingual Captioning for Writing and Vocabulary Enhancement. Alicante Journal of English Studies, 29, 229–248. https://doi.org/10.14198/raei.2016.29.13

Talaván, N., Lertola, J., & Fernández-Costales, A. (2024). Didactic Audiovisual Translation and Foreign Language Education. Routledge.

Talaván, N., Lertola, J., & Ibáñez, A. (2022). Audio description and subtitling for the deaf and hard of hearing Media accessibility in foreign language learning. Translation and Translanguaging in Multilingual Contexts, 8(1), 1–29 https://doi.org/10.1075/ttmc.00082.tal

Talaván, N., & Rodríguez-Arancón, P. (2014). The use of interlingual subtitling to improve listening comprehension skills in advanced EFL students. In B. Garzelli & M. Baldo (Eds.), Subtitling and Intercultural Communication. European Languages and beyond (pp. 273–288). InterLinguistica ETS.

Talaván, N., & Tinedo-Rodríguez, A. J. (2023). Una mirada transdisciplinar a la Traducción Audiovisual Didáctica. Hikma, 22(1), 143–166. https://doi.org/10.21071/hikma.v22i1.14593

Tinedo-Rodríguez, A. J. (2022a). La enseñanza del inglés en el siglo XXI: Una mirada integradora y multimodal. Sindéresis.

Tinedo-Rodríguez, A. J. (2022b). Producción fílmica, género, literatura y traducción audiovisual didáctica (TAD) para el aprendizaje integrado de contenidos y lenguas (AICLE). DIGILEC: Revista Internacional de Lenguas y Culturas, 9, 140–161. https://doi.org/10.17979/digilec.2022.9.0.9155

Tinedo-Rodríguez, A. J., & Frumuselu, A. (2023). SDH as an AVT Pedagogical Tool: L2, Interculturality and EDI. Translation and Translanguaging in Multilingual Contexts, 9(3), 316–336. https://doi.org/10.1075/ttmc.00116.tin

Vanderplank, R. (1988). The value of teletext sub-titles in language learning. ELT Journal, 42(4), 272–281. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/42.4.272

Vanderplank, R. (2016). “Effects of” and “effects with” captions: How exactly does watching a TV programme with same-language subtitles make a difference to language learners? Language Teaching, 49(2), 235–250. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444813000207

Zabalbeascoa, P., Sokoli, S., & Torres-Hostench, O. (2012). Conceptual framework and pedagogical methodology. CLIPFLAIR Foreign Language Learning Through Interactive Revoicing and Captioning of Clips. European Union. http://hdl.handle.net/10230/22701